The modern knowledge worker spends countless hours at desks, making ergonomic office setup crucial for long-term health, comfort, and productivity. Poor ergonomics contributes to musculoskeletal disorders, eye strain, fatigue, and decreased work quality. Conversely, properly designed workspaces reduce injury risk, minimize discomfort, enhance focus, and support sustained productivity. Understanding ergonomic principles and implementing evidence-based workspace optimization creates environments where people can work comfortably and effectively for years without cumulative physical damage.

Understanding Ergonomic Principles

Ergonomics—the science of designing environments to fit human capabilities and limitations—aims to reduce physical stress and optimize human performance. Proper ergonomics maintains neutral body positions, minimizes repetitive strain, reduces sustained static postures, and supports natural movement patterns throughout the workday.

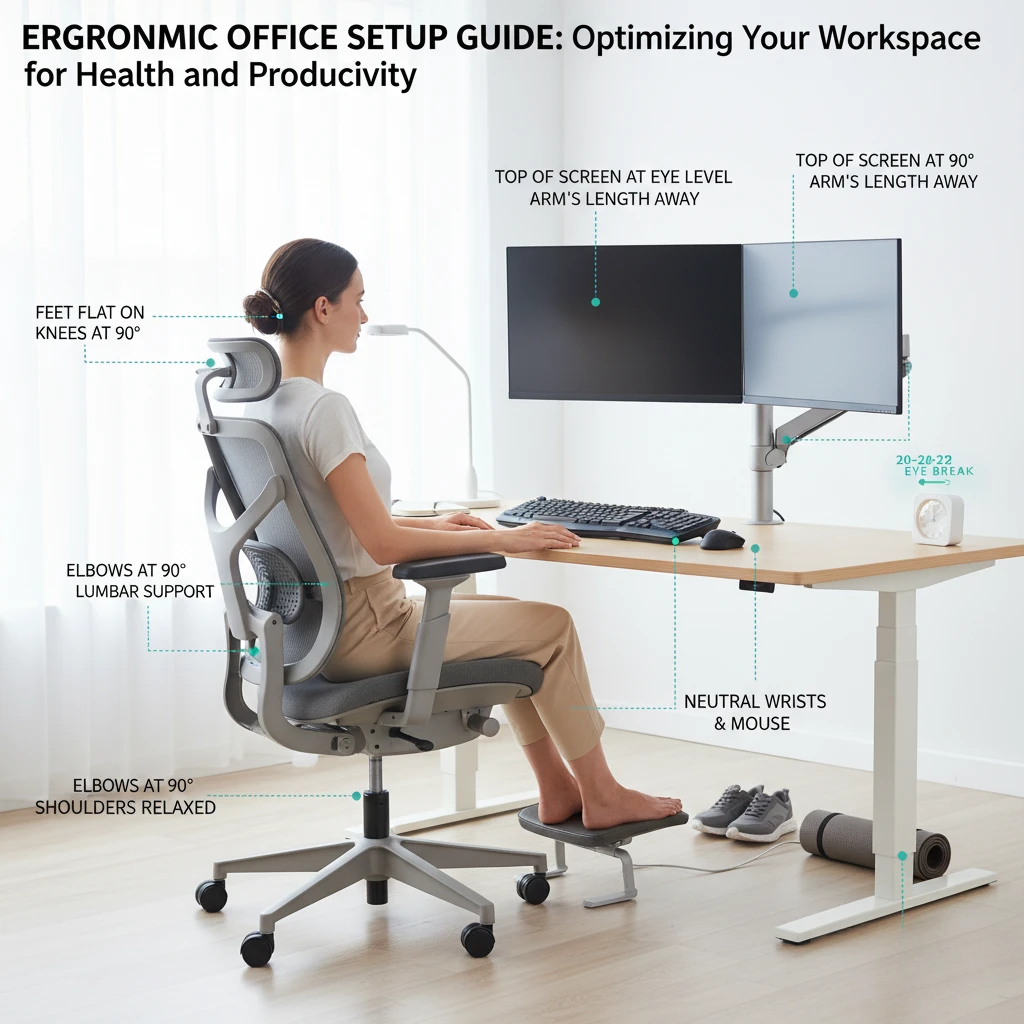

Neutral posture forms the foundation of ergonomic setup. This position minimizes stress on muscles, tendons, and joints while allowing efficient muscular function. Key neutral posture elements include:

- Head and neck: Balanced directly over shoulders, not jutting forward or tilted

- Shoulders: Relaxed, not elevated or hunched forward

- Elbows: Close to body, bent approximately 90-120 degrees

- Wrists: Straight, not bent upward, downward, or sideways

- Back: Supported by chair backrest, maintaining natural spinal curves

- Hips: Positioned slightly higher than knees, thighs parallel to floor

- Feet: Flat on floor or footrest, knees bent approximately 90 degrees

Maintaining these positions reduces mechanical stress on the body. Even small deviations, sustained over hours daily for years, can cause cumulative damage resulting in chronic pain and reduced function.

Chair Selection and Configuration

Office chairs represent the most critical ergonomic investment, as chair quality directly affects posture, comfort, and health. Proper seat height allows feet to rest flat on the floor (or footrest) with thighs parallel to the ground and knees bent approximately 90 degrees. This position promotes healthy circulation and reduces pressure on the back of thighs.

Lumbar support maintains the spine’s natural inward curve in the lower back. Without proper support, people tend to slouch, flattening this curve and placing excessive load on spinal discs and ligaments. Adjustable lumbar support should contact the lower back approximately at belt level, providing gentle forward pressure that maintains natural curvature.

Seat depth should allow 2-4 inches between the seat edge and the back of knees. Seats too deep force users forward away from backrest support or create pressure behind knees that restricts circulation. Seats too shallow provide inadequate thigh support.

Armrests should support forearms lightly while maintaining relaxed shoulder position. Armrests too high force shoulders upward, creating tension. Armrests too low provide no support or cause users to lean sideways. Adjustable armrests accommodate different body proportions and work tasks.

Essential Chair Features:

| Feature | Importance | Optimal Configuration |

|---|---|---|

| Seat Height Adjustment | Critical | Feet flat on floor; thighs parallel to ground |

| Lumbar Support | Critical | Adjustable height and depth; supports natural lower back curve |

| Seat Depth | Important | 2–4″ clearance behind knees; adjustable for leg length |

| Armrest Adjustment | Important | Height & width adjustable; supports forearms without lifting shoulders |

| Backrest Recline | Beneficial | Adjustable angle with lock; supports varied postures |

| Seat Material | Beneficial | Breathable fabric; cushioning without excessive softness |

Recline capability enables postural variation throughout the day. Static positions, even optimal ones, become uncomfortable over time. Reclining 10-20 degrees periodically reduces spinal loading and allows muscles to relax. Some ergonomists recommend “dynamic sitting”—making small position adjustments frequently rather than maintaining perfectly static posture.

Desk Height and Monitor Positioning

Desk height determines arm and shoulder position. Standard desk heights (28-30 inches) suit people of average height but may be inappropriate for shorter or taller individuals. When seated with proper posture, desk surface should allow forearms to rest parallel to the floor with shoulders relaxed. Elbows should bend approximately 90-120 degrees when hands rest on the keyboard.

Height-adjustable desks accommodate different body proportions and enable transitioning between sitting and standing. Sit-stand desks have gained popularity, allowing users to alternate positions throughout the day. While standing desks alone don’t guarantee health benefits, alternating between sitting and standing reduces prolonged static loading and promotes movement.

Monitor height profoundly affects neck posture. Top of the monitor screen should align approximately with or slightly below eye level. This positioning allows viewing the screen with neutral neck posture—head balanced over shoulders without tilting forward, backward, or rotating. Monitors positioned too low force users to tilt heads forward, placing enormous stress on neck muscles and cervical spine.

Monitor distance typically should be 20-30 inches from eyes, roughly arm’s length. This distance allows comfortable viewing without excessive eye focusing effort. Larger monitors may need greater distance. Individuals should be able to see the entire screen with minimal head movement and read text comfortably without leaning forward.

Monitor angle should tilt slightly backward (10-20 degrees from vertical) to maintain perpendicular viewing angle when the screen is positioned at proper height. This reduces glare and maintains comfortable viewing without neck extension.

Multiple monitor setups require special consideration. Primary monitor should sit directly in front of the user. Secondary monitors should angle inward slightly, positioned where frequent viewing doesn’t require sustained neck rotation. Users who reference secondary monitors constantly should position them more centrally, accepting that neither monitor is directly ahead.

“Ergonomic optimization isn’t about achieving perfect static posture—it’s about creating workspace configurations that support varied, comfortable postures and regular movement throughout the workday.” – Dr. Daniel PAT

Keyboard and Mouse Ergonomics

Keyboard positioning should allow typing with straight wrists and relaxed shoulders. Keyboards placed too high force wrist extension (bending upward) and shoulder elevation. Most standard keyboards have adjustable feet on the back edge—these should remain down, keeping keyboards flat or tilted slightly away from the user.

Split ergonomic keyboards position hands at more natural shoulder-width distance, reducing ulnar deviation (sideways wrist bending). Tenting keyboards (raising the center) promotes more neutral forearm rotation. These modifications may feel awkward initially but can reduce strain for users with existing discomfort or those prone to repetitive strain injuries.

Keyboard trays mounted below desk surfaces can improve ergonomics when desks are too high. These trays should position keyboards at elbow height with adequate space for mouse alongside keyboard. Trays should be stable, adjustable, and allow negative tilt (front edge higher than back) to maintain neutral wrist posture.

Mouse placement directly beside the keyboard at the same height minimizes reaching. Mice positioned too far forward force shoulder flexion and forward reaching. Vertical mice rotate the forearm to a more neutral “handshake” position, potentially reducing strain on the forearm muscles.

Keyboard shortcuts reduce mouse dependence, decreasing repetitive hand movements. Learning common shortcuts for frequent tasks reduces cumulative strain from repetitive clicking and cursor movement.

Lighting and Eye Strain Prevention

Display-related eye strain affects most computer users, causing tired eyes, headaches, blurred vision, and difficulty focusing. Proper lighting and display configuration significantly reduce these symptoms.

Ambient lighting should illuminate the workspace without creating screen glare or high contrast between the display and surrounding environment. Extremely bright rooms make screens appear dim, forcing users to increase brightness to uncomfortable levels. Very dark rooms create high contrast between bright screens and dark surroundings, contributing to eye fatigue.

Positioning monitors perpendicular to windows prevents direct glare and reduces backlit conditions that force screens to compete with bright background light. Anti-glare screen filters reduce reflections when environmental control is insufficient.

Display brightness should match ambient lighting levels. Screens shouldn’t appear as light sources in the environment but rather as illuminated surfaces comparable to surrounding brightness. Color temperature affects comfort—warmer (yellower) tones are often more comfortable than cool blue-white light, particularly during evening hours.

The 20-20-20 rule helps prevent eye strain: every 20 minutes, look at something 20 feet away for 20 seconds. This brief break allows eye focusing muscles to relax. Software applications can provide reminders, though simply developing the habit of periodic distance viewing is effective.

Font size and contrast should enable comfortable reading without leaning forward. If users frequently squint or lean toward displays, increasing font size or adjusting screen distance improves comfort. High contrast between text and background reduces eye strain—black text on white backgrounds or white text on dark backgrounds both work well.

Blue light filtering, either through software (f.lux, Night Shift) or physical screen filters, may reduce eye strain and improve sleep quality by reducing blue light exposure, particularly in evening hours. While research on blue light’s effects continues, many users report subjective comfort improvements.

Movement and Variation

Static postures, regardless of ergonomic optimization, become uncomfortable over extended periods. The human body is designed for movement, and prolonged stillness causes discomfort and health risks. Regular movement breaks should occur at minimum every 30-60 minutes.

Simple movements include standing, walking briefly, stretching, or performing different work tasks requiring position changes. Even standing for 1-2 minutes per hour provides benefits. Longer breaks—5-10 minutes every 1-2 hours—enable more substantial movement and mental recovery.

Microbreaks—brief pauses of 30 seconds to 1 minute—can be incorporated even more frequently. These might involve looking away from the screen, performing gentle stretches, or simply changing sitting position slightly. Microbreaks don’t significantly impact productivity but reduce cumulative strain.

Active workstations including treadmill desks, cycle desks, or balance boards promote movement during work. These work best for tasks like reading, attending meetings, or phone calls rather than precise work requiring fine motor control. Even modest activity—walking at 1-2 mph—provides health benefits over sedentary work.

Postural variation throughout the day protects against repetitive strain. Slightly different sitting positions, occasional standing, and varied work tasks that require different postures distribute physical loading across different structures rather than concentrating stress repeatedly on identical tissues.

Laptop and Mobile Device Ergonomics

Laptops present inherent ergonomic compromises—when the screen is at appropriate height, the keyboard is too high; when the keyboard is properly positioned, the screen is too low. Laptop stands elevate screens to proper viewing height while external keyboards and mice enable appropriate input device positioning. This configuration essentially converts laptops to desktop ergonomics.

For temporary laptop use without accessories, adjusting chair height to bring eyes level with the elevated laptop screen is preferable to hunching over a low screen. Short duration (under 30 minutes) can tolerate compromised positioning, but regular laptop use requires proper setup.

Tablet and smartphone use typically involves sustained neck flexion (head tilted forward) when devices are held in laps. Bringing devices to eye level by raising hands reduces neck strain but causes shoulder and arm fatigue. Tablet stands or props that elevate devices to more neutral viewing angles represent better solutions for extended use.

“Text neck”—chronic neck pain from sustained forward head posture during mobile device use—has become increasingly common. Raising devices closer to eye level, taking frequent breaks, and performing neck stretches help mitigate these issues.

Accessories and Supportive Tools

Footrests benefit shorter individuals whose feet don’t rest flat on the floor with proper chair height. Footrests should be stable, slightly angled, and large enough to allow varied foot positions. Adjustable height footrests accommodate different leg lengths.

Document holders position reference materials at similar height and distance as monitors, preventing sustained downward gaze or frequent refocusing between vastly different distances. These benefit users who frequently reference paper documents while typing.

Wrist rests are controversial—while they can support wrists during breaks, resting wrists on supports while typing may increase contact pressure and carpal tunnel compression. Wrists should float above keyboards during active typing, with hands and forearms forming relatively straight lines.

Monitor arms enable precise monitor positioning and easy adjustment. Single monitor arms typically cost $100-300 but provide infinitely adjustable positioning surpassing what fixed stands allow. This flexibility enables optimal configuration for different body sizes and work tasks.

Anti-fatigue mats for standing desk users provide cushioning that reduces leg and foot discomfort during prolonged standing. These mats encourage subtle movements and weight shifts that promote circulation and reduce static loading.

Workspace Layout and Organization

Frequently used items should sit within easy reach—the primary work zone extending roughly 16 inches from the body. Items requiring reaching beyond this zone cause repeated strain. Organizing workspaces to minimize reaching and twisting protects against cumulative injury.

Cable management prevents clutter that interferes with proper positioning and creates tripping hazards. Cable trays, clips, and sleeves organize cables neatly, allowing furniture adjustment without cable tangles limiting movement.

Temperature and air quality affect comfort and productivity. Ideal office temperatures typically range from 68-74°F, though individual preferences vary. Adequate ventilation, humidity control (30-50% relative humidity), and air filtration improve comfort and reduce respiratory irritation.

Acoustics significantly impact concentration and stress levels. Excessive noise interferes with focus, particularly for complex cognitive tasks. Noise-canceling headphones, white noise systems, or acoustic panels can improve sound environments in shared spaces.

The Future of Ergonomic Workspace Design

Emerging technologies promise more adaptive, intelligent workspaces. Posture monitoring systems using cameras or wearable sensors provide real-time feedback about position and reminders to adjust posture or take breaks. These systems learn individual patterns and provide personalized recommendations.

Smart furniture with automated adjustments can save preferred positions for different users or activities, automatically adjusting when users approach or switch tasks. Integration with calendars could prepare workspace configurations for scheduled activities—standing for meetings, optimal sitting position for focused work.

Biometric monitoring tracking physiological stress indicators—muscle tension, heart rate variability, eye strain—could prompt breaks or workspace adjustments before discomfort develops. This proactive approach prevents problems rather than reacting to pain.

Virtual and augmented reality workspaces introduce new ergonomic challenges—headset weight, limited peripheral vision, virtual workspace configuration. Research into VR ergonomics is developing guidelines for healthy extended use of immersive environments.

As Dr. Daniel PAT, I emphasize that ergonomic optimization is fundamentally about respecting human physiology while supporting productive work. Our bodies evolved for varied movement and natural postures, not sustained static positions focused on screens. Good ergonomics doesn’t eliminate all discomfort—no single position remains comfortable indefinitely—but it minimizes unnecessary strain and supports varied, sustainable work practices. Investment in ergonomic setup pays dividends in comfort, health, and sustained productivity. While perfect ergonomics is unattainable, thoughtful attention to setup principles creates workspaces where people can work comfortably and healthily for decades rather than accumulating injury that limits capacity and quality of life.

This article is part of Exobiota’s content series exploring practical applications of technology and design principles for healthier, more productive work environments.